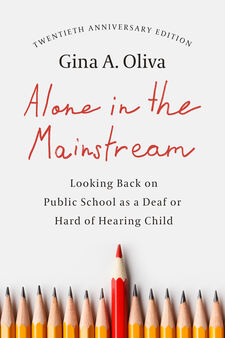

An Interview with Gina A. Oliva, Author of "Alone in the Mainstream: Looking Back on Public School as a Deaf or Hard of Hearing Child"

Gina A. Oliva is retired from a thirty-seven-year career at Gallaudet University, and is now enjoying life in historic Old Greenbelt, Maryland, with her husband, Joe, and their cat, Noelle. She plays pickleball, rides her bike, walks around the neighborhood with Noelle (no leash!) and sings/signs fun songs with a local ukulele group. She continues to support summer camps for deaf kiddos with both her money and her time. Her book, Alone in the Mainstream, newly released in a twentieth-anniversary edition, raises awareness of the social isolation often experienced by deaf and hard of hearing children in mainstream educational settings.

GUP: Can you share about your personal journey and what inspired you to write Alone in the Mainstream? When did you realize your story needed to be told?

GAO: Some readers might overlook the fact that my father was hard of hearing and, therefore, I very much identified with him. Arriving at Gallaudet College as a senior, having spent three years at a small liberal arts college in Maryland, I came to realize that I could live my life differently than he had. He was unwilling to learn any sign language, despite all my efforts to convince him that it would be a good thing. He thought a deaf person could not be a college president. When he died on my 46th birthday, it struck me that somehow, I must tell our story. I became determined to spotlight the difference between his choices and my choices.

GUP: How did Public Law 94-142/IDEA impact your education and social experiences? In what ways do you feel these laws have succeeded or failed in providing a “Least Restrictive Environment” for deaf and hard of hearing children?

GAO: Interestingly enough, I first learned of Public Law 94-142 while working in the office of Edward C. Merrill, then president of Gallaudet College. It was my job to scan the federal register for items Dr. Merrill should respond to. I recall being appalled and thinking “Oh no! The poor kids will have to go through what I did. No, no, no!!” And even more interestingly, when I told Dad about this, he expressed alarm, shaking his finger in that Italian way, “Not good…that will hurt their spirit!”

So maybe while resisting my efforts for him and the family to learn to sign, he nevertheless, somewhere in his being, understood the deep, pervasive, and ubiquitous impact of being “alone in the mainstream.”

GUP: What role has developing a deaf identity and being part of a deaf community played in your life?

GAO: Well, let’s just say that I can’t overstate the impact of my late-coming awareness of the deaf community. I was 20 years old when this part of my life journey began at Gallaudet College (now University). Fifty-plus years later, I can only be grateful for this. The “signing environment” allowed me to become everything I was capable of — to reach my potential.

GUP: In the twenty years since the first edition of your book, what changes, if any, have you observed in the education and inclusion of deaf and hard of hearing students in mainstream schools?

GAO: The lives of deaf and hard of hearing children have become even more language/social deprived.

To me, this is a direct result of what I call “Big Cochlea” — the mechanisms in place that indoctrinate families, mostly mothers, regarding their responsibilities during the 0 – 5 years to religiously train their implanted infants and toddlers to “learn to speak.” If the child does not “learn to speak,” the onus is on the caregivers rather than on the implant. See Laura Mauldin’s 2016 publication, Made to Hear.

GUP: Why do you believe it’s crucial for deaf and hard of hearing children to have access to sign language and a deaf community?

GAO: The bias against signed languages predates us by centuries. The world at large doesn’t recognize signed languages as the epitome of what makes us human. We will see in years to come that AI cannot “read” or fully “translate” a human, native, signed language user’s utterances into a spoken language.

Individuals who think differently or do not recognize the amazing richness of signed languages are, in general, themselves not fluent in any signed language, and are therefore very unqualified to judge the value of signed languages. They just plain have no clue, nor does anyone else who does not know a signed language.

Unfortunately, too many such individuals are within the entrenched “early detection and intervention” system. There is a direct line from identification to implantation. There is a road map that all the players know, and they steer the parents along. I hope no one tries to sue me for saying that, but it is the truth.

Why is this so terrible? Because no one can predict how much “success” any individual child will have with spoken language. There are many factors involved with the child’s ability to actually use an implant, not the least of which is the parent’s ability to provide constant day-in and day-out, hour-by-hour attention to speech and listening. Made to Hear and Laura Mauldin’s subsequent journal articles are must-reads for anyone considering implanting their child, as well as any practitioners in related fields.

I call upon any and all organizations (schools, professional organizations, hospitals) that even tacitly discourage the use of signed languages to publicly reverse their positions to endorse and support bilingualism (a spoken language and a signed language) for all deaf children, including implanted ones. Any stance that denies or minimizes the fact that bilingualism is best for both language and social development is harmful to deaf children and their families.

GUP: How can families and educators better support deaf and hard of hearing children today?

GAO: I think the most important thing is for everyone to become involved, at least at the state level, to reduce both language deprivation and social deprivation. There is already legislation passed or initiated in certain states that require language evaluations at various milestones for infants, toddlers, and preschoolers.

To remedy social deprivation, each child must have the opportunity to spend time with other deaf/hard of hearing children. Weekend and summer programs that bring the children and/or their families together for mutual support and learning must be written into every child’s IEP. Since the state insists that deaf children be in their local schools (and thus so many of them “alone in the mainstream”), the state must address the rampant social deprivation that any deaf or hard of hearing adult, young and old, can tell you about.

Yes, of course, you need to assist and advocate for your own deaf child/ren. But lack of involvement at the state level only allows the untenable situation to continue.

GUP: What are some of your current passions and activities, and how do they connect to your advocacy for deaf and hard of hearing kids?

GAO: Most people who know me know I have been advocating for summer camps and programs ever since the first edition of Alone in the Mainstream was published in 2004. This work continues as I mentor or occasionally advise younger friends who are still in the trenches. And make donations.

Beyond that, I have a natural propensity for fitness, sports, art, and even music, so I am often inviting deaf friends to pickleball, drum circles, and ukulele gatherings in our current little “NORC” (Naturally Occurring Retirement Community). The local pickleball regulars almost all know their numbers now for scoring. They get excited that they can sign the numbers 1 – 11 and sometimes 12 or higher!!! And they learn signs for “lucky,” “bad,” “great,” etc. It’s fun!

And best of all they see that we deaf are not “alone in the mainstream,” but rather we have dynamic conversations and a camaraderie that many hearing individuals lack.

One deaf person there, invisible.

Two deaf people there, visible but could be pitied.

Three plus deaf people chatting it up, wow that looks like fun!

Comments