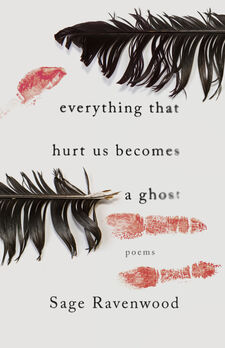

An Interview with Sage Ravenwood, Author of "Everything That Hurt Us Becomes a Ghost"

Sage Ravenwood is a deaf Cherokee woman residing in upstate New York. She is an outspoken advocate against animal cruelty and domestic violence. Her work can be found in The Temz Review, Contrary, Pioneertown Literary, Grain, The Familiar Wild: On Dogs and Poetry, The Rumpus, Lit Quarterly, and more. Everything That Hurt Us Becomes a Ghost is her exploration of the lingering, resurgent trauma of familial violence and the machinations of colonialism.

GUP: Everything That Hurt Us Becomes a Ghost is your first poetry collection. Could you share a little bit about your journey to becoming a writer?

SR: This is going to sound surrealist in its approach, but I just sat down one day in 2019 and wrote my first poem. From there, I continued writing. I found poetry afforded me the luxury of saying more with fewer words. My journey doesn’t follow everyone else's, of course. I’ve been lucky enough to have poetry continuously picked up by literary magazines online and offline. I’ve also had my share of rejections. For me, writing isn’t a set amount of hours or some dedicated schedule. Writing is free-flowing, letting the poem speak instead of forcing words onto the page. As far as my journey is concerned, I didn’t stop writing after that first poem. I have a file full of poems that will never see the light of day, but there wouldn’t be a collection unless I continued to have something to say. Everything That Hurt Us Becomes a Ghost is the culmination of four years of deep diving into myself and pulling out the trauma and love it takes to survive. I wanted people to be able to read that process in its entirety. It’s a heavy carrying, but it’s also freeing.

GUP: Which poem in the collection is the most meaningful to you?

SR: This is actually a hard question. The majority of the poems I’ve written are centered around events in my life. That’s like asking which was more or less painful or enriching among your memories. Having said that, “Red Dressing” comes immediately to mind. The entire poem is centered around MMIW (Missing Murdered Indigenous Women) and that movement. I wanted to bring more awareness to something that continues to affect Indigenous communities across the US and Canada. To remove the trope of someone saying, I’m only one person, what can I do? One person is one more voice demanding someone listen. Indigenous shouldn’t have to remind the world we’re still here. Not in this day and age.

GUP: On your website, you write, “Poetry is a rebellious act these days.” Could you share your thoughts about that?

SR: Thinking of poetry as a rebellious act started with my first poem, “Bullet Tithe,” published in Glass: A Journal of Poetry – Poets Resist. I had written “Bullet Tithe” on the day of the El Paso, Texas, shootings. I had so much that I needed to pull out of me writing that piece around the horror of what unfolded. Soon after, in November, I had another piece published in the same journal. “Wash It All Away” was about the loss of innocence. There’s a line that stands out in that poem: Let the hierarchy surrender. Let the will to live be tender. Isn’t that what rebellion is, in a sense? Holding up a fist over your head in the form of words and saying, I don’t like the way the world is right now; this is what it has done to me; this is the change I want to see in the world. In the same breath, it’s the ability to still see glimpses of something beautiful strewn in among the chaos despite the rebellion raging inside.

People tend to think of poetry as their grandmother’s flowery prose or some Shakespearean lament they’re forced to learn in school. I’ve always thought it to be darker, like the nursery rhymes we grew up with; although delightful to recite, they contain some “not-so-pretty” warnings interlaced between the words. I believe poetry is that in today’s world. We have something to say; we’re protesting what’s happening around us; we have our own truth to share. Poetry is rebellious in that it’s pulling the veil back and saying, in a not-so-gentle way, look. That rebellious nature is something I’m finding more prevalent in today’s poetry than ever before.

GUP: How does the creative process work for you? Do you start with a story you want to tell? Or a feeling you’re trying to express? Something else? How does it take shape?

SR: For me, there’s no process or “aha” moment. I think for anyone who chooses to be present in their everyday life, there’s always going to be something they’re trying to process on an emotional level. That’s writing for me, in a nutshell. With my deafness, I tend to feel as though I’m locked inside my head with my thoughts, and I can’t escape. There’s no everyday background noise to distract or anything of that nature. So writing tends to take shape in that way. If there’s something that stays with me or sits heavy on my heart, I write. In this way, there isn't a “no vacancy” sign flashing in my head, preventing me from moving through my days. I know the latter statement is a broad landscape to decipher. So let’s return to the earlier question about poetry being a rebellious act: I’m writing about whatever touches heavily on my life; I’m writing to escape what I can’t change; I’m writing to be a better person. I’m writing life. That’s the process, and it’s rebellious in the freedom that it provides.

GUP: Is writing a healing process for you?

SR: I think it is for anyone who chooses to use it in that way. Writing is therapeutic in that it gives you the ability to say what you’re unable to say out loud. I’ve always been loud. Having said that, there are things that we keep locked inside for fear of how the rest of the world would react if they knew. Talking about the sexual abuse I survived wasn’t necessarily one of those things I was loud about. Through poetry, I found a way to say what I needed in fewer words: to delicately take the reader through each line by the hand and say, look here, did you see what happened there, without slamming my reality upside their heads. Writing gave me the ability to show something I’d long kept hidden, unabashedly. That was therapy for me.

GUP: What advice do you have for emerging writers?

SR: Tell your story, your truth, the way you want to be heard. The world has enough jagged edges that will cut into you daily. If this is something you want to do, do it. It’s not an easy route to take. At the end of the day, not everyone is going to like what you write or what you have to say. That’s okay. Write for yourself. Don’t write for popularity or to fill some empty salvos, find what’s genuine, what speaks to you. I’m not going to sit here and say everyone can do this or that it’s easy. I’m not going to discourage you either. If this is what you want, the only person stopping you is you. Writing is probably the most difficult journey I have ever undertaken, and that’s saying a lot if you’ve read about any of the number of things I’ve survived. I’m still writing, despite. Be your own champion. There are a lot of us out there, but that doesn’t mean you can’t or shouldn’t leave your own mark on the world.

GUP: What do you hope readers take away from your book?

SR: Honesty. A sense that not everything is as it seems, and even if you do get a glimpse into something deeper, keep looking. I can’t really speak from my reader’s perspective. What I can say is this: It’s possible to survive the monsters in human guise. I hope each and every reader comes away knowing a little something about what it’s like to spend some time in someone else’s skin, to see life through their eyes. I think if we can all do that, see the world through someone else, no matter how temporarily, taking off the linear view lens, maybe we might be kinder, more empathetic human beings. It’s a lot to ask of a book, I know, but it’s a start.

Comments