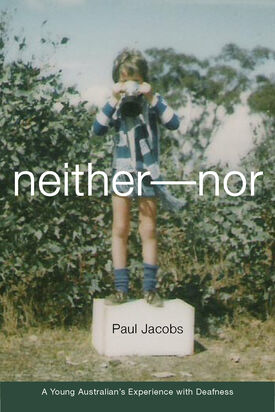

Neither–Nor

A Young Australian's Experience with Deafness

First Edition

In the fifth Deaf Lives volume, Jacobs tells of searching in Australia and Europe for an identity that has yet to be invented, as being neither deaf nor hearing, but an in-between.

Description

The Fifth Volume in the Deaf Lives Series

Born in Melbourne, Australia, in 1974, Paul Jacobs lost his mother when he was three months old. When he was five, he lost most of his hearing. These two defining events formed the core of his being. He spent the first two decades of his life “coming to terms with being neither Deaf nor hearing — a neither/nor, an in-between — and a person with a social identity that had yet to be invented.” His memoir, Neither—Nor: A Young Australian’s Experience with Deafness, recounts this journey.

Jacobs excelled in sports and the classroom, but he never lost awareness of how he was seen as different, often in cruel or patronizing ways. His father, a child psychologist, headed a long list of supportive people in his life, including his Uncle Brian, his itinerant teacher of the deaf Mrs. Carey, a gifted art teacher Mrs. Klein, who demanded and received from him first-rate work, a notetaker Rita, and Bella, his first girlfriend. Jacobs eventually attended university, where he graduated with honors. He also entered the Deaf world when he starred on the Deaf Australian World Cup cricket team. However, he never learned sign language, and frequently noted the lack of an adult role model for “neither—nors” such as himself.

Still emotionally adrift in 1998, Jacobs toured Europe, then volunteered to tutor deaf residents at Court Grange College in Devon, England. There, he discovered a darker reality for some deaf individuals — hearing loss complicated by schizophrenia, Bonnevie-Ullrich Syndrome, and other conditions. After returning to Australia, Jacobs recognized what he had gleaned from his long journey: “Power comes from within, not without. Sure, deafness makes one prone to be stigmatized. Yet having a disability can act as a stimulus for greater personal growth, richer experiences, and more genuine relationships.”

Paul Jacobs is a doctoral candidate in the Deafness Studies program at the University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.